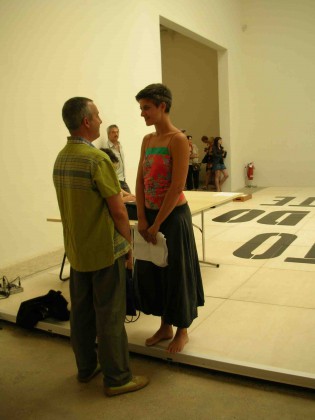

The gesture of inverted commas as protection against the anger of the audience. Image: Michelangelo Miccolis and Francesco Paolo Ferrara in “The Artists Without Works, A Guided Tour Around Nothing”

“If you are an artist without works, maybe you should not make exhibitions”, a lady art critic told me. Well, I don’t, I thought, or rather, it depends what you mean by exhibitions; but I admit, her logic is spotless.

“If you insult the audience, then you will keep people out of the museums!” the same critic told me. Mmmmmmmmmmmm – I thought.

These are the insults the artist without works addresses to the audience:

“You wax figures. You impersonators. You bad-hats. You troupers. You tear-jerkers. You potboilers. You foul mouths. You sell-outs. You deadbeats. You phonies. You educated gasbags. You cultivated classes. You befuddled aristocrats. You rotten middle class. You lowbrows. You people of your time.”

It is hard to imagine someone being offended by such poetic epithets. If while they are being said someone with a very attractive and friendly face is shaking your hand, you are very likely to even be pleased with it. But this performance was not done to please anyone – it is just a side effect.

Nevertheless I had to smile with the comment of the art critic – “Because of artists like you, people keep out of the museums”. First: this Biennale proves that enormous masses of people seem interested enough in contemporary art to pay 20 euros entrance. Second: it would not be a bad thing to keep a few people out of the museums – one can hardly walk in them anymore. Third: I believe you would overjoy any of the “classic and greatest” avantgarde artist (think of Debord, think of Tzara) if you told them their work would keep people out of the museums for good. Can anyone think that the dadaist artist, or if you push me, the cubist artist, had as an aim to attract flocks of pleased people to see their work? Smiling masses delighted in extreme to see Les Demoiselles d’Avignon?

It is, I admit, paradoxical. I hope to have soon a conversation with Francesco Matarrese on:

La lotta contro l’istituzionalizzazione dell’arte e la lotta contro le illusioni della pittura erano rimaste per tutto il novecento gli obiettivi di fondo della volontà d’arte delle avanguardie artistiche. Presto però questi obiettivi si erano trasformati in promesse non mantenute, in sogni infranti. Le origini di questo fallimento sono da ricercare negli insanabili contrasti tra consenso e potere durante la Rivoluzione francese. Questi, si accentuarono nel ’48, quando l’artista borghese si sentì tradito dall’istituzione. Il modello del Diciotto brumaio di Karl Marx può essere ancora utile, come suggerisce Thomas Crow in Modern Art in the Common Culture (1996), per interpretare la complessa dinamica tra l’avanguardia e le numerose repliche neoavanguardistiche. Nel contrasto tra gli ideali del ’48 e le promesse non mantenute della Francia del tempo è da ricercare la prima ragione della nascita di un’arte borghese come avanguardia di contestazione dello stesso potere borghese. Un’arte dunque di resistenza e opposizione ma anche di ambigua complicità.

(http://www.centroriformastato.org/crs2/IMG/pdf/passaggio_al_lavoro_vivo.pdf)

“A bourgeois art as avant garde of refusal of the same bourgeois power. An art of resistance and opposition but also of ambiguous complicity”.

I have been observing quietly, together with Charles Filch, the success of, for instance, The Sphinx.

Charles Filch was smiling as he saw how people were really delighted at the questions of the Sphinx, how they pretended to walk around casually but were really trying to catch her attention; and then he turned to me and said:

“It really works, doesn’t it?”

And me, with a worried face:

– Yes, it is a crowd pleaser…

– Oh, come on… don’t be so hard on yourself! Enjoy the joy of people!

So I worry if they like it, and I worry if they don’t – still I pretend not to care.

“The audience, these poor wage-earners who see themselves as property owners, these mystified ignoramuses who think they’re educated, these zombies with the delusion that their votes mean something.”

Again quoting from “The Artist Without Works: A Guided Tour Around Nothing”.

As Maria Elena (Fantoni), one of the performers of Instant Narrative (/instant-narrative/), put it today: “I see them and I play with them when I describe them, they react to what I write, they act for me, but to me they are like people in a dream, I feel I know them but I know them only in the dream. So when I bump into the very same people in the street, I feel shocked”.

“Anche lui ha una macchina fotografica in mano ma non scatta foto. La biennale è chiusa. I due uomini lasciano lo spazio espositivo mentre uno dei due fa vedere all’altro qualcosa dalla macchian fotografica.”

Challenging the audience or the public can be done in many ways. Maybe one of those ways is to offer a portrait of themselves, describing them, talking to them, trying to involve them, even bothering them.

But this (including when you may be able to bother the audience) proves that you’re giving attention to the public because people are an important part of the art or the art system.

Either way, one way or another, you are giving importance to the public. But not in a popular or populist way, because you’re being demanding or exigent with the audience. Some populist people could say you’re elitist. It’s what they say when they want to attack someone who is not a populist or who is not afraid of speaking directly to the audience.

Requiring something from the audience is always a form of respect for them.

Demanding something from the audience means that you respect the public and even that you trust them.

We are witnessing the clash of two speeches on the techniques and media perception of the world. If the audience takes refuge in the arts critics media and its means of asserting their ability to build the world, the artist/poet claims the anti-artistic construction as form of creative resistance. A creative trial always convert a critical problem in an artist operation.

A creative artist operation always will be counteroperation.

Some artists are able to find a third option seeking a view from the other side of the mirror. But it´s not easy to escape the dilemma between the image and counter-image. I prefer to think that the most worthy and interesting outlet for the creative acts means to bring your own bomb that could expose your work to self-destruction. Thus the audience is denied, especially the fawning presence of experts who always fly over the success and failure. Very few want to go further.